The year 1954 and the months immediately before and after was a crucial time, a true watershed for twentieth-century Italian painting.

This was when a numerous group of Italian artists made the leap to full artistic maturity. The centre of the scene was Rome, where Afro, for one, after a prolonged journey through the Scuola Romana in the 1930s and the neo-Cubist period in the immediate post-war years, capitalized on his American experience and found his artistic language in a verism that is mere memory and a colour that plunges into the abyss and then slowly resurfaces. While Toti Scialoja, his friend and contemporary, found in a new medium – applying paint with a cloth rather than the brush – his path to an abstract art ever more heavily charged with confession and mystery. And Antonio Corpora began to arrive at his “heterodox Informalism”.

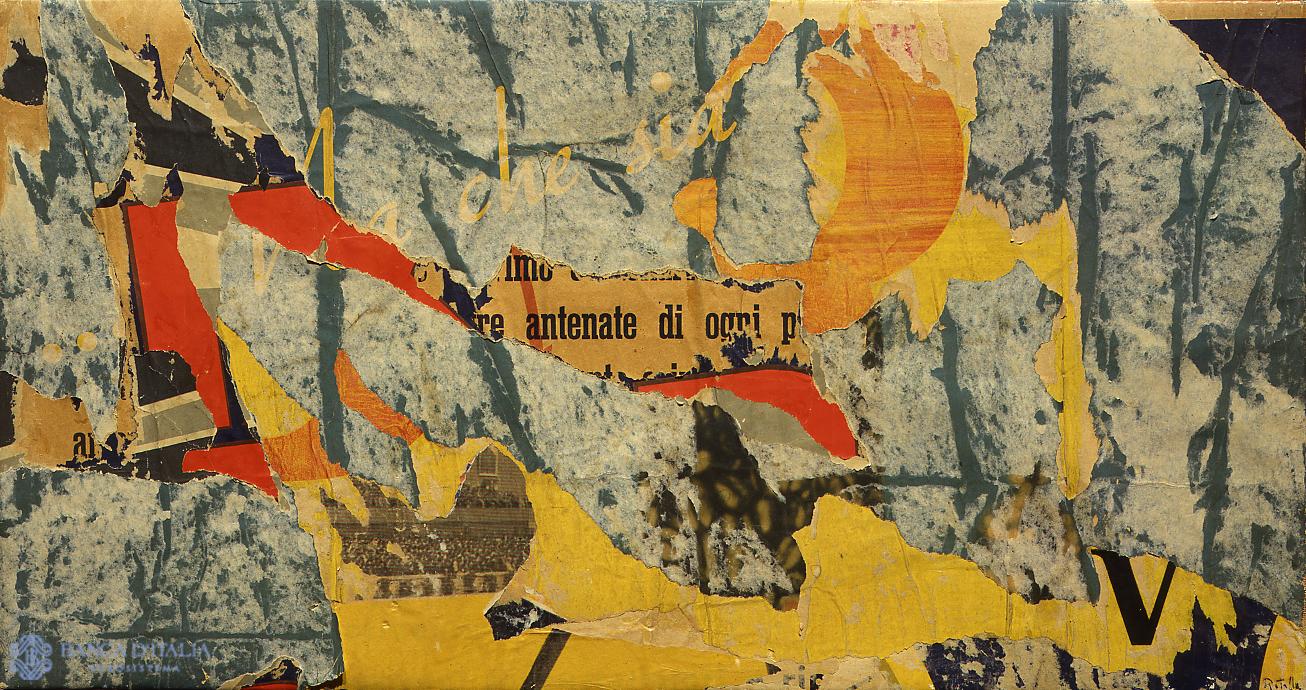

Another example, also in Rome, was the set of “young artists” – Piero Dorazio and Achille Perilli, Carla Accardi and Antonio Sanfilippo, Giulio Turcato and Pietro Consagra – who had grouped together in 1947 under the banner of Forma, reworking a sort of neo-Cubism soon modified by the neo-concrete teachings of Magnelli and other artists from France. They too, after sharing an artistic language that had made them practically interchangeable, found their own, sharply individual ways. In 1954, too, Mimmo Rotella first began ripping posters from the walls of Rome as a form of art, while Salvatore Scarpitta emerged from the Expressionist mould that had governed his early work.

Also in 1954, to broaden our gaze to the northern part of the peninsula, Francesco Arcangeli published in Paragone, Roberto Longhi’s review, the essay that ratified the aggregation of the “last naturalists”, headed by Ennio Morlotti, a painter who had been a member of the two most influential groups in Italian art in the aftermath of the war: Fronte Nuovo delle Arti and the Group of Eight. These formations were definitively disbanded by now – another feature characterizing the mid-1950s: mistrust of the unity of intention that can arise from the sharing of a poetics and a common strategy.

To give yet another example, in Venice Emilio Vedova and Giuseppe Santomaso came to full artistic maturity outside the abstract-concrete synthesis of the “Eight”. As did the junior Tancredi. In Milan, as Mario Nigro’s rigorous abstraction reached its acme, Bepi Romagnoni gave voice, in the brief course of his lifetime, to his painful “existential realism”.

Only two Italian artists can be said to have foreshadowed the new course of art prior to the watershed of 1954: Alberto Burri and Lucio Fontana. Burri had ripped and resewn his “sacks” in 1952, while in 1949 Fontana – from a different, older generation – had already begun to punch holes in his papers and canvases: gestures that constituted a radical rupture with tradition but with which neither of these seminal artists intended to abandon painting.

1954-1970: forme dell’astratto

1954-1970: Forms of the Abstract

Works of art

Tre sabbie

Three double imprints rise vertically in the composition, saturating the space. The painting is serious, intransigent, almost hostile; the three bodies are raised on a bed of thick material binding the sand to the colour pigments using a fast-acting vinyl adhesive and appear as red and white tongues of flame arranged sequentially on the canvas.

20th century AD

Painting

Abstract

Spazio totale n. 5

Geometric shapes descend, one upon the next, in the field of the canvas. Inside, they are densely crisscrossed by lines intersecting at right angles; and in the minute spaces that these crossings highlight, they are punctuated by additional small signs, all rigorously the same.

20th century AD

Painting

Abstract

Untitled

Scarpitta’s painting, by now, is definitively removed from any reference to reality: in the packed, saturated, congested syntax of bodies and volumes, which no longer imitate any truth of nature, the colour explodes, manifold and resounding: whites, reds, and blacks engender a conflagration on the mantle of the ochre background.

20th century AD

Painting

Abstract

Senza titolo

Tancredi once wrote, “I think that in my paintings you can see that space is curved” and this motto seems to fit this painting perfectly, where myriad light and wavering dark blades gather in the centre of the composition and then leave in all four directions, providing the sensation of a convex body that gravitates in space.

20th century AD

Painting

Abstract

Rinascere

A lake of colour, nothing more, forms the image of this painting. Varying through hundreds of tonally attuned declinations, yellows, earths, ochres, and more cautious oranges saturate the surface, evenly occupied, stretching towards the viewer, opening no perspective towards an illusion of depth.

20th century AD

Painting

Abstract

Reticolo

“Forms of pure, lyrical invention interweave and overlap to the rhythm of emotion, creating a space that is poetic space” – so wrote Palma Bucarelli, director of the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome, in her introduction to the vast one-man room dedicated, for the first time, to Turcato at the Venice Biennale.

20th century AD

Painting

Abstract

Quadrato in evoluzione

Within this small painting, there unfolds a vast, practically incommensurable space; wafted towards an indefinite “beyond” – one might say – by the mad swirling of a propeller, almost the only note of loud, bright colour in a sea of whites and greys, that revolves at the centre of the composition, as if gathering in and driving in all directions the feeble breath of breeze that turns it.

20th century AD

Painting

Abstract

Pietra miliare

A white fire occupies the centre of the image, a ghostlike apparition in the pall of greys and ochres. But everything has become a blur by now: the forms, no longer confined by the drawing, have been reduced to ”pulsating bodies woven from light and graphic rhythms,” as Nello Ponente wrote when presenting the 21 works from these years that hung in the vast room dedicated to the artist in the Venice Biennale of 1960.

20th century AD

Painting

Abstract

Piccola immagine di legno

At the centre of this oblong canvas, the clash and explosion of a clump of matter, blacks greys oranges, as if some brief, blind flight had crashed into a barrier raised without warning. The image, whose title Piccola immagine di legno (“Small image of wood”) Moreni inscribed on the back of the canvas according to a practice begun in 1960, is shot through, agitated, by the violence that is a constant feature of this artist’s work.

20th century AD

Painting

Abstract

Notturno

Floating, almost organic bodies draw near to one another, brush one another, intertwine; the tenuous, matte colours, in tonal accord, from which a short red note rings out high up in the composition, push the bodies to the epidermis of a surface that becomes the painting’s only space.

20th century AD

Painting

Abstract

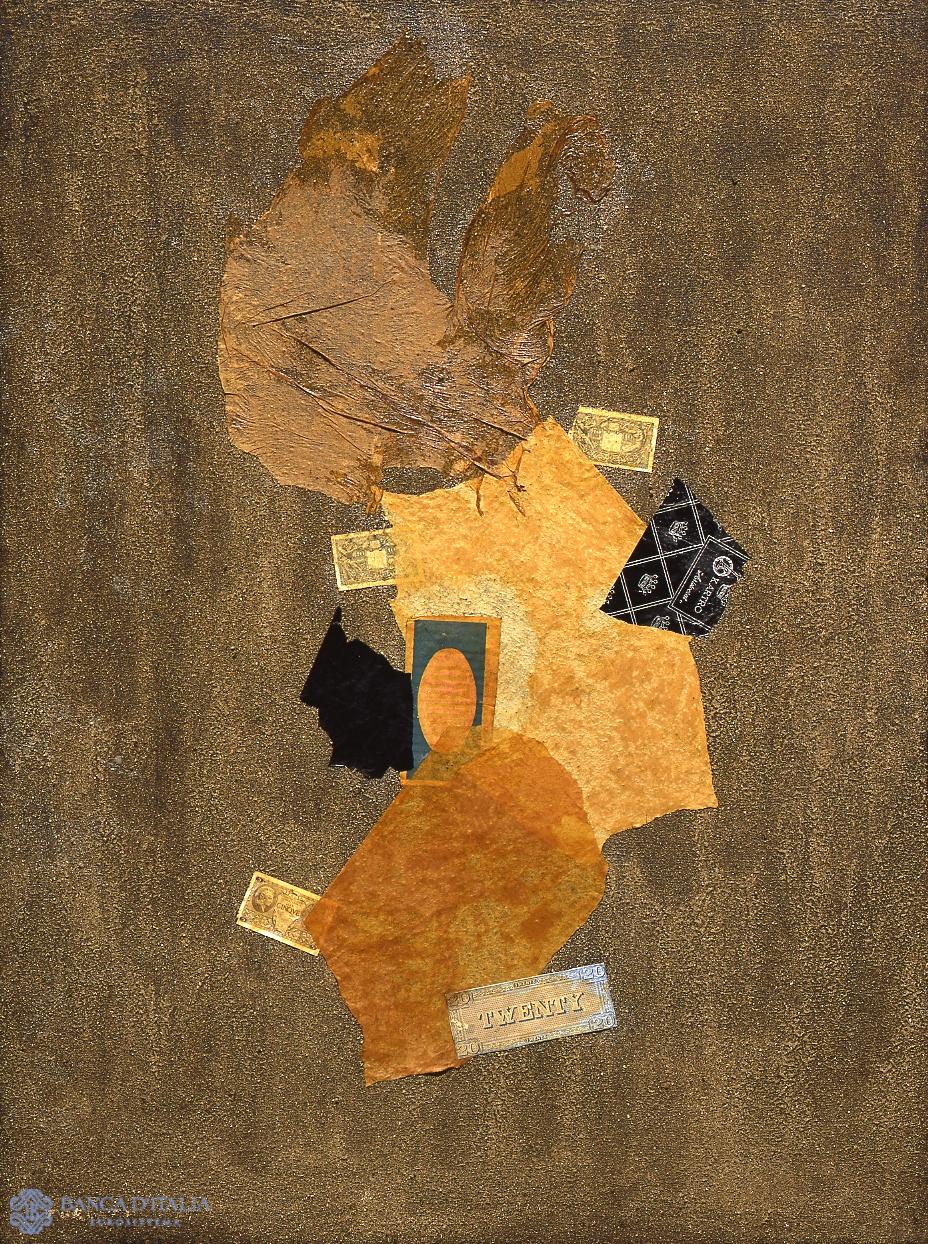

Lenzuolo di San Rocco

A strange vertical figure composed of scraps of paper and paper money, rising enigmatic above a sandy background, without shadow. Once again, the image stubbornly seeks the surface, shuns all illusion of depth that would bind it to the world.

20th century AD

Painting

Abstract

Immagine del tempo ’59, n. 3

Within the vast turmoil of this oblong canvas nearly three metres tall, blacks race over a mantle of whites; a torrid yellow – almost a heart – crackles at the centre of the composition, which is ruptured throughout by hiccups, clashes, violence.

20th century AD

Painting

Abstract

Fondo rosso

On a red base, luminous yellow lines going in all directions intersect and collide in a state of agitation in which there is full expression of a kind of art that shuns a balanced or peaceful composition of its forms.

20th century AD

Painting

Abstract

Figura

Scattered over the entire surface of the painting, the soft, mellow colours – which appear to emanate from the touch of palest pink at the centre of the composition – writhe in the open and potentially infinite space of the pictorial field; they are free from all ties; no probe of perspective anchors them to any point.

20th century AD

Painting

Abstract

Due di febbraio

On two registers, which occupy the higher and lower sections of the composition, is a series of imprints that Scialoja has made on the canvas using oiled paper, drenched in paint and then “beaten” onto the surface of the previously coloured canvas.

20th century AD

Painting

Abstract

Dimostrazione a New York (Vigilia a New York)

The small canvas is shot through, almost shaken, by elongated and lacerated forms loaded with vibrant and varied colours – black, red, white, orange – which stretch along the horizon and soar upwards. In the inextricable heap of the mangled figures, it is possible to make out several inscriptions.

20th century AD

Painting

Abstract

Composizione

Geometrical forms intertwine on the surface, occupying the entire area of the painting: again, it is the idea of a horizon around which the composition is arranged and develops that governs the spatial breakdown of the image. And it is this formal intention pursued here by the painter which distances the work from the notion of an academy of the abstract, the risks of which Romiti appears to sense.

20th century AD

Painting

Abstract

Composition sur une courbe algebrique

This is an abstract work typical of the 1950s, when Severini went back to Futurism after the protracted figurative interlude of the interwar years. The allusion to an algebraic curve testifies to the artist’s lively interest in the relationship between form and “number,” already manifest in his “Du Cubisme au Classicisme” (1921).

20th century AD

Painting

Abstract

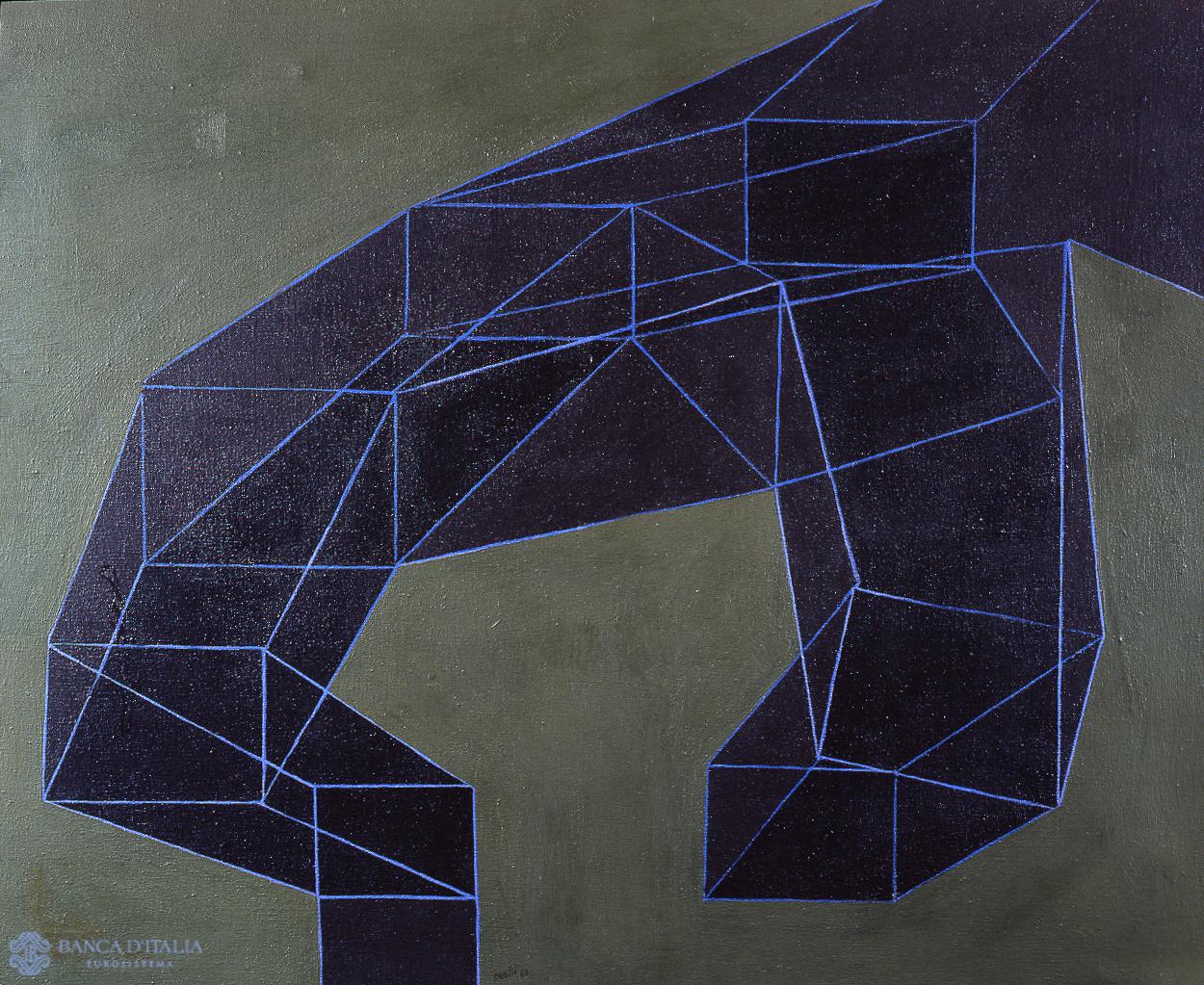

La civetteria dell’astrazione

A large, dark form, composed of the interlocking of numerous irregular polygons, extends across the canvas surface; untouched by shadows and therefore lacking any depth of its own, it appears to tumble forward, apprehensively, from above to below.

20th century AD

Painting

Abstract

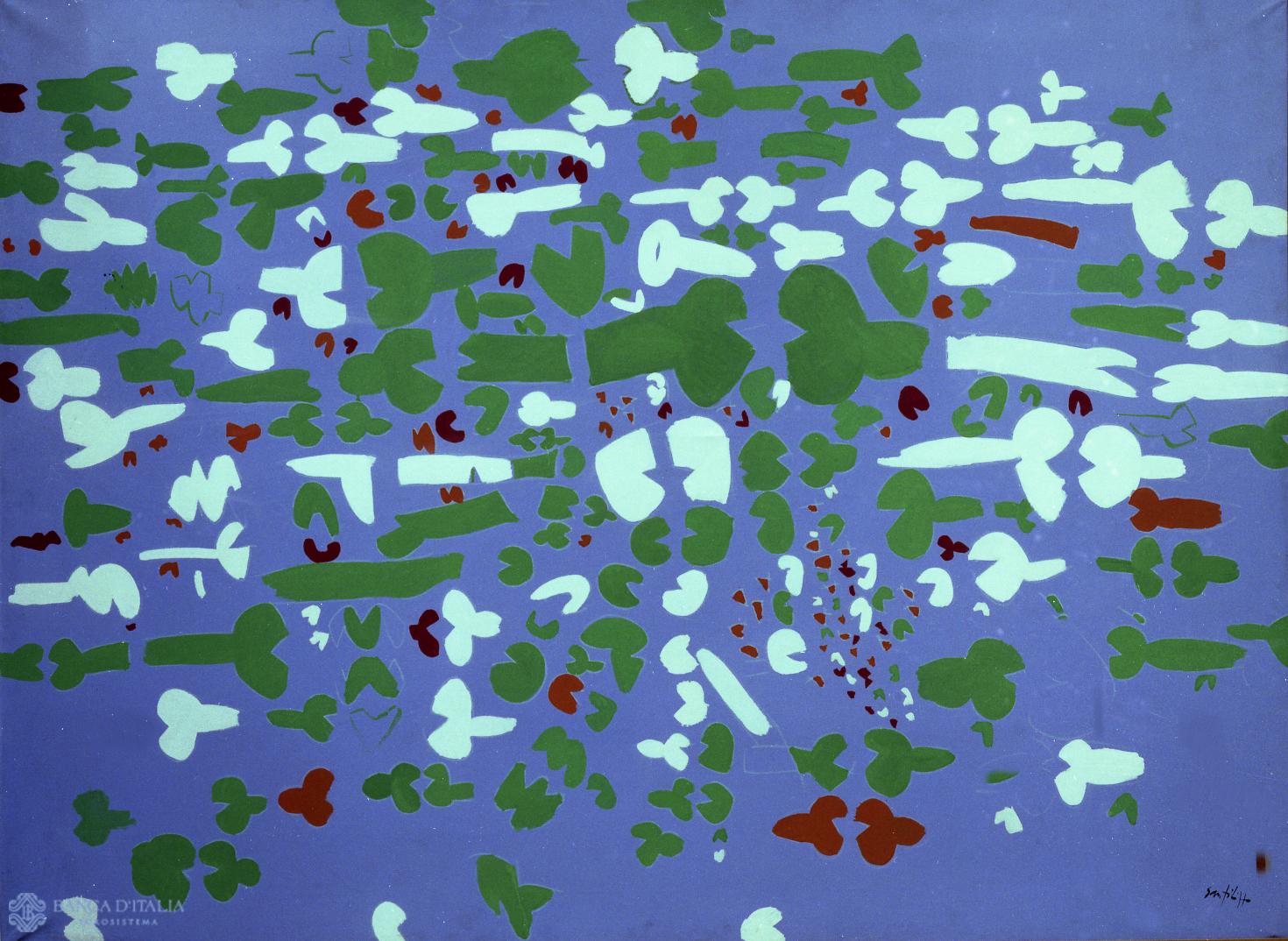

Blu verde azzurro

A hundred figures wander in pursuit of one another on the monochrome surface. It is as if they were weaving a dance: untouched by shadow and with no chiaroscuro to evoke their weight and volume, they appear to play at saturating the space in an irrepressible riot of colour, with whites, greens and blues ringing out.

20th century AD

Painting

Abstract