The vicissitudes of the period stretching through the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s produced, in Italy as throughout Europe, a clear-cut phase in the history of modern and contemporary art. Artists came onto the scene who had been born between 1905 and 1920 and so had not participated in more than marginal fashion in the artistic revolution carried out by the historical avant-garde, nor in the subsequent “return to order”. At the same time, older artists who had been more deeply involved in the “return” continued to work, but they too took new paths.

The older of these artists truly fulfilled their artistic intentions during this period, while the younger generations came to full maturity or at least gave the first substantive indications of the directions their artistic quest would take. For old and young alike, the essential intellectual and cultural drive was the rejection of the “return to order”. For experienced artists, this rejection translated above all into a rejection of the dogmatic, closed-minded, celebratory aspects of the Novecento school. One of the key formal consequences was renewed attention to the tonalism expressed in the work of Giorgio Morandi and a more “intimate” emotionalism. For the younger, refusal translated into a sweeping claim of freedom from any kind of “ism” with an explicit programme, like the “manifestos” of the avant-gardes and the Novecento school.

From France, where the second generation of Surrealists, among them Alberto Giacometti, came to the fore together with such new figurative artists as Balthus, to Germany, where the various attempts to found a new type of realism involved not only a historic figure like Otto Dix but also the “magical realism” of Christian Schad and Franz Radziwill, Europe offered a full range of alternatives. The protagonists in this phase revisited the past – including the recent past of the avant-garde – in the light of their radical search for new forms of expression.

In a milieu that had been liberated, freed from excessive programmatic prescriptions, the reciprocal contamination of artistic languages became an important theme. The situation in Italy also reflected the new intellectual climate, and the Bank of Italy’s collection offers a fair selection of works from some of the leading artists of this lively period: older painters such as Francesco Trombadori and Riccardo Francalancia, on the cusp, so to speak, of the “return to order” and the new milieu; Antonio Donghi, Italy’s own “magical realist”; such singular, evident outsiders as Luigi Bartolini and Renato Paresce; Carlo Levi and Roberto Melli; and the fertile artistic community of the nation’s capital, in and around the Roman School grouping such artists as Fausto Pirandello, Mario Mafai, Alberto Ziveri and Giovanni Stradone, each of whom exemplified a significant strand of interwar painting.

Tra le due guerre, al di là del “ritorno all’ordine“

The Interwar Years, Beyond the “Return to Order”

Works of art

Veduta di Vallerano

The picture shows a view of a mediaeval town, a typical subject of Roman painting between the two wars, from Trombadori to Francalancia and Ziveri too. The fragment of the town appears in the left-hand part of the painting, starting from a close-up blocked by an enormous buttress.

20th century AD

Painting

Landscape

Ritratto di Lina

The work shows the face of a woman, in a three-quarters pose looking to the right-hand side of the picture. The woman is wearing a sort of loose jacket, the tones of which contrast with those of the face, rosy and soft, delicately infused by a light that colours the cheeks.

20th century AD

Painting

Portrait

Paesaggio laziale

This Lazio landscape, dated 1935, is ruled by a classical, orderly, simple composition, in which from the foreground the road seems to move slowly away towards the background, almost entirely shut off by trees.

20th century AD

Painting

Landscape

Paesaggio fiorentino

To the right we see a stone wall, bending sinuously towards the background, where it appears suddenly to block a dense cluster of buildings, behind which a bell tower and church dome are visible. To the left, a tree twists, as if in response to the torsion of the wall facing it.

20th century AD

Painting

Landscape

Paesaggio di Ciociaria

This landscape of southern Lazio, done in 1934 and thus in the central years Trombadori’s career, shows a composition founded upon the sharp contrast between the dark, dense vegetation clinging to a ridge of rock on the left and the town stretching up the hillside on the right.

20th century AD

Painting

Landscape

Paesaggio con elci

This “Landscape with Holm-oaks” (1928) was painted during a phase when Donghi had basically fully developed his figurative programme. Stasis, the feeling of fatal stillness of trees which, with their dense foliage, occupy the entire field of vision, springs from the avid gaze of the view in search of the tiniest detail.

20th century AD

Painting

Landscape

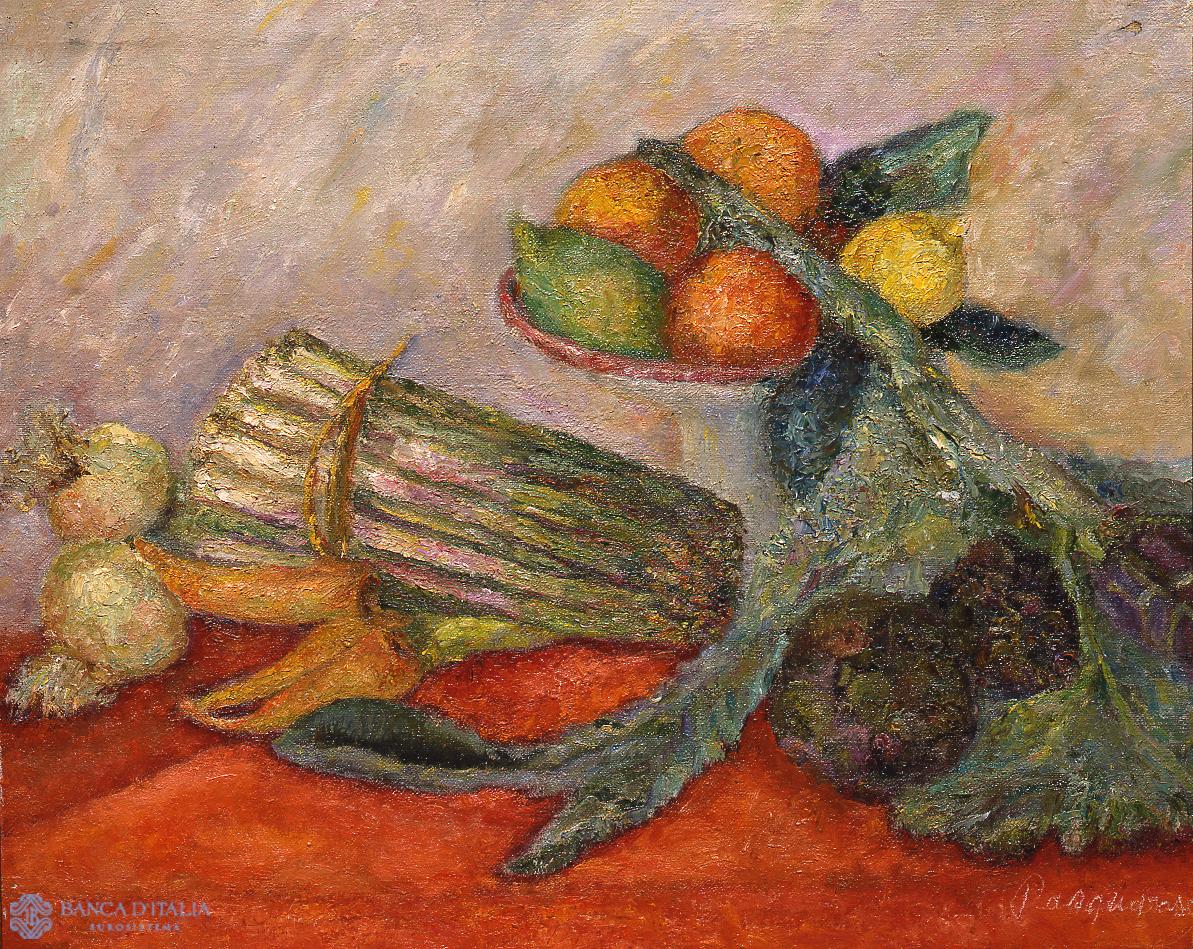

Natura morta con frutta e asparagi

On a table covered with a red cloth stands a fruit bowl, in front of which lies a bunch of asparagus whose tips point towards the left-hand side of the painting. The composition does not appear to give any importance to the harmonious arrangement of the subjects.

Painting

Still life

Mercato di notte

The work shows a small crowd gathered round a stand. The salesman, in the foreground, is talking to the shoppers, who form a circle interrupted only in the foreground, as if to emphasize the presence of the salesman, a dark figure standing out against the fully illuminated surface of the stand.

20th century AD

Painting

Figurative

Marina di Celle Ligure

This seascape, dated 1951, is divided into several distinct swathes: the widest is that of a blue sea from which a band of clouds of a lighter blue appears to emerge on the left of the picture, rising diagonally towards the sky and spreading into a fringe on the right.

20th century AD

Painting

Landscape

Largo di San Rufino n. 16

This partial view of a medieval village shows a slope, which on the left side reaches a building only just barely visible, while on the right we see two houses at the roadside.

20th century AD

Painting

Landscape

La fenêtre

This 1926 painting depicts the view from a window over a small terrace with a set of objects, presented to the viewer not as bearing witness to a mundane event but as a highly recherché still life (a “stille Leben” or “silent life”).

20th century AD

Painting

Landscape

Fabrica di Roma

In this depiction of a town in Lazio Donghi ignores the settlement itself in favour of a purely natural space, with no human presence: a sort of gap between two trees, two hulking masses at each side of the canvas, opening in the centre to a horizon formed by the silhouette of a mountain.

20th century AD

Painting

Landscape

Enrico e il divano

The male figure is painted almost face on; behind him the shape of the divan on which he is leaning in a detached manner is outlined schematically. The chromatic range is dominated by pinkish tones that vary until they become nearly white in response to the light.

20th century AD

Painting

Portrait

Donne allo specchio

Two women seen in profile turn their faces and bodies towards a mirror that reflects a third person who is not shown directly. The total “ordinariness” of the interior scene, which is clearly working-class, is underlined by the two women’s clothes and by their almost passive immobility, which strengthens the radical absence of any idea of “posing”.

20th century AD

Painting

Figurative

Casolari in campagna

In this painting, rich vegetation fills the foreground behind which there is a clearing leading to some buildings spread out on two levels. In the background, beneath a lively sky, in which an intense blue forcefully contrasts with a reddish glow, a group of dwellings appears between the hill, which closes them in, and a line of trees on the left-hand side.

20th century AD

Painting

Landscape