Divisionism meant “dividing” colours, setting them alongside one another on the canvas rather than mixing them on the palette; that is, supplanting a physical mixture with an “optical” mixing, realized by the eye of the viewer. As a tendency within Italian painting, Divisionism arose after 1885 and lasted for about three decades. Its leading figures were Giovanni Segantini, Gaetano Previati and Angelo Morbelli, whose joint exhibition of their works at the Milan Triennale in 1891officially launched the movement.

In formal terms, Italian Divisionism – influenced by the frayed, figure-dissolving light used by Daniele Ranzoni, Tranquillo Cremona and Luigi Conconi – differed from its somewhat earlier French counterpart of Pointillisme or neo-Impressionism. The difference was that the Italian Divisionists put colour on the canvas with streaked brushstrokes (Previati, Pellizza da Volpedo) or matrix clots (Segantini), while the Pointillists (led by Seurat and Signac) brought them together as points, small dabs of colour. The rigorous theory of the French artists formed a basis common to the two schools of Divisionism (both of which had scientific inclinations) drawn from the laws of colour developed by the chemist M.E. Chevreul and the writings of the art critic Charles Blanc. Blanc, whom Seurat knew before the work of Chevreul, had developed the theory of optical mixing, i.e. that separate dabs of pure pigments (not blended on the palette), when they are set one next to the other, form purer, more vibrant colours in the eye of the viewer. Chevreul’s laws were more detailed, dividing all colours into “primary” (blue, yellow, red) and “secondary” (all the others, consisting of various mixtures of the three primaries). The primary colour not serving as one of the ingredients of a secondary colour was termed the latter’s “complement” (e.g., green, which is created by a mixture of blue and yellow, is the complement of red). Every colour projects its complement on the colour on which it borders; two complements enhance one another.

In Paris, at the height of Positivism, there was a resurgence of belief in the power of science among the most celebrated modern literati, writers and philosophers. The most enthusiastic supporters of the new credo were such luminaries as Hyppolite Taine, the Goncourt brothers, and Zola. Flaubert issued his famous appeal for the integration of art and science: “Art and science, so long separated … must tend to a close union if not to merge into one another”.

On the Italian side, the theorist was Gaetano Previati, whose Principi scientifici del divisionismo (1906) maintained that the new technique “reproduces the additions of light through the methodically minute separation of complementary hues”. The most rigorous follower of the Divisionist principle was the Turin artist Pellizza da Volpedo. Other Divisionists were Grubicy de Dragon (who together with his brother provided precious support for the spread and acclaim of the movement), Baldassare Longoni, Carlo Fornara, Plinio Nomellini, Camillo Innocenti, Enrico Lionne and Arturo Noci, not to mention Giacomo Balla, whose free application of Divisionist principles and post-Impressionism in general influenced his students, Boccioni and Severini, whose Futurist painting brought out the logical consequences of Divisionism.

Divisionismo

Divisionism

Works of art

Veduta di Arosio (Brianza)

This view of Arosio is a painting of the highest quality, produced just before the majestic high-mountain landscapes that characterized Longoni’s last period. The refined chiaroscuro fabric of the work hinges on the tall, dark tree in the foreground, which serves as repoussoir of the eye towards an evanescent horizon.

19th century AD

Painting

Landscape

La punta di Pallanza

Daniele Ranzoni’s few, sporadic landscapes have as theme Lago Maggiore, where the artist was born and lived. In this intense view of the lake, Ranzoni offers a sample of his refined sensitivity to light and colour. The painting dates to his last years (he died in 1889).

19th century AD

Painting

Landscape

Paesaggio sotto la neve

This large painting clearly shows the influence of Giovanni Segantini, not only in its impressive dimensions but above all in its subject, an immense snowy landscape. Maggi displays his lusty power of construction, presenting us, in an imposing frontal view, with the majesty of the mountain.

20th century AD

Painting

Landscape

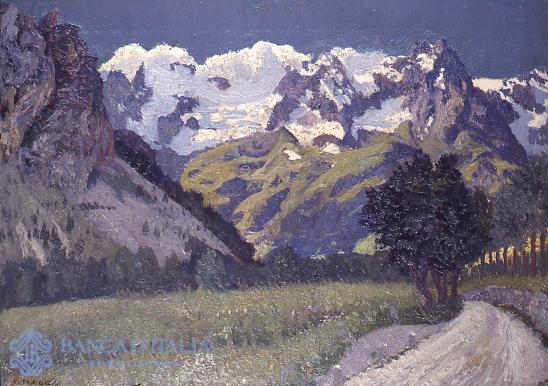

Paesaggio montano

The subject here is a snow-capped mountain chain: a potent barrier stretching right across the composition, while in the foreground a dirt road runs up into the gorge. At the roadside, dark trees contrast with the yellowish greens of the overlooking mountain slopes and the paler, impasto tones of the trail.

20th century AD

Painting

Landscape

Paesaggio montano

The crystal-clear depiction of this landscape is a forceful reminder that what was central to the poetics of Divisionism was the veristic search for reality as the aim of painting. The novel method of composition, emulating the immediacy and method of the photographic snapshot, is surprising, startling.

20th century AD

Painting

Landscape

L'orto dell'artista

In this gossamer view opening onto a panorama that stretches to the far-distant horizon, Morbelli returns to one of his favourite themes, his beloved landscape from his country house at La Colma di Rosignano.

20th century AD

Painting

Landscape

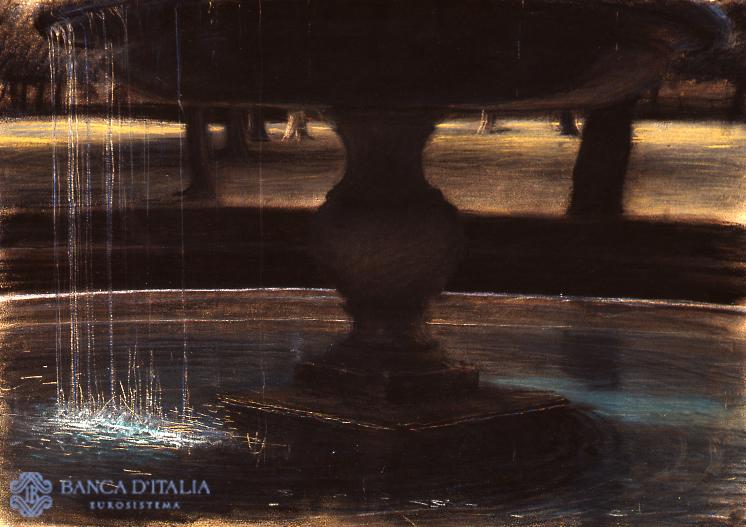

Fontana (che piange)

An authentic masterpiece of bravura, this pastel still belongs to Balla’s Divisionist period. The streaky brushstrokes are horizontal, distributed in dense tangles of material. Here the artist makes the most of his ability to depict the play of light on forms.

20th century AD

Painting

Landscape

Dalla Colma

Morbelli came to Divisionism late. He was nearly forty, in fact, when he took part in the Milan Triennale of 1891 together with Segantini and Previati, marking the debut of Italian Divisionism. This painting is one of his later works, done between 1918 and 1919, the year of his death.

20th century AD

Painting

Landscape

Casa di riposo Bonacossa a Dorno Lomellin

A dim light filters in through two big windows on the left, enveloping seven figures in a large, plain room. The unadorned scene reproduces, as in a snapshot, a painful, lonely moment of silence for these old women, gathered in the old people’s home and portrayed, at the end of the day, in the pointless onflow of their lives.

20th century AD

Painting

Figurative

Autoritratto

Before he joined the Futurist movement, Giacomo Balla’s art was post-Impressionist, updated in his own, highly personal Divisionist mode. This 1902 self-portrait is a masterpiece that demonstrates the directions in which he was moving at that time.

20th century AD

Painting

Portrait

Amalfi

Cesare Maggi is known mainly for the fine quality of his early Divisionist painting, but the freshness of this view from the sea is certainly on a par with the artist’s first period. Here he appears to have already completed his turn towards a somewhat more traditional painting, an art less attuned to the new, but already seemingly old-hat, experimentation.

Painting

Landscape