Futurism was the most important avant-garde art movement of early 20th-century Italy. It is often seen as a violent tidal wave that swept away all traditional forms and produced a new vision that exalted speed and motion. Yet while these were in fact the fundamental themes of Futurism, set out by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the movement’s founder, in the inaugural Manifesto published by Le Figaro in Paris in 1909, the artists who adhered to the programme (who issued a series of manifestoes of their own for the renovation of painting, sculpture and architecture beginning in February 1910) had to come to grips, aside from the subjects they chose, with the much more complicated problems of a new form in which to express them, with the power to work a radical metamorphosis of the then-dominant style of painting. These artists were Umberto Boccioni, Gino Severini, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo and Giacomo Balla. Balla, older than the others and from Turin but living in Rome, introduced Boccioni and Severini to his own post-impressionist Divisionist approach, which also embraced Carrà and Russolo. At first their painting was a violently expressive forcing of the colourist principles of Divisionism (their writings exalted “congenital complementarism” and asserted that all the colours in a setting were reflected in the face and body of the figures). Later, learning of the development of Cubism in 1911 and 1912 (the year of the Futurist exhibition in Paris), they adopted the principles of de-composition and synthesis of forms, based above all on the concept of “simultaneity”: of past (memory) with present; of figure with surroundings, interacting, imbued with dynamism taken as universal principle. On this point, however, Balla’s approach (extended to photography by Anton Giulio Bragaglia) conflicted with that of Boccioni. Balla sought to render motion as a series of “snapshots” taken in successive moments, while Boccioni imagined dynamism as the play of forces surging out of the figures and echoing in the surroundings. Russolo took Balla’s approach, while Severini and Carrà (who basically split off from Marinetti’s movement as early as 1914 or 1915) came closer to Boccioni’s conception, Carrà in particular paying great attention to Cubism. Other essential aspects of early, figurative Futurist art were “polymaterialism” – the use of materials alien to the traditional techniques of painting, begun by Boccioni’s sculptures in 1912-15, continued by Balla and Depero as part of the manifesto “Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe” (1915), and further developed, assiduously and inventively, by Enrico Prampolini as part of the “second Futurism”. This so-called second Futurism, which many not entirely wrongly consider as a declining phase of the movement after the death of such leading lights as Boccioni and Sant’Elia and the defection of Carrà and Severini, was characterized above all by Areopittura, whose aerial views capitalized on the airplane, the newly dominant means of transportation that the early Futurists could only intuit.

Apart from painting and sculpture, Futurism was also applied to literature, in the wake of Marinetti (who theorized not only “words in liberty” but also automatic writing and abstract onomatopoeia), as well as architecture, music, cinema, theatre, dance, acting and oratory. The Futurist movement thus styled itself as the first and only “total” avant-garde and exerted a powerful influence on twentieth-century art, from Dada to Surrealism and finally Pop art.

Il Futurismo

Futurism

Works of art

Simultaneità organica

A typical work of the “Second Futurism” inspired by Prampolini, this painting seems to contrast the “simultaneity” of times and spaces with another, “organic simultaneity”: the symbiosis of the forms of man with those of nature and the cosmos.

Painting

20th century AD

Abstract

La seggiola dell'uomo strano

In 1929, Balla had just moved into his new house at number 39b, Via Oslavia, as his daughter Elica wrote: “There was a terrace with so much sun. … In the early part of our time there … my father painted the terrace door in La seggiola dell’uomo strano, one of his last Futurist works.”

Painting

20th century AD

Abstract

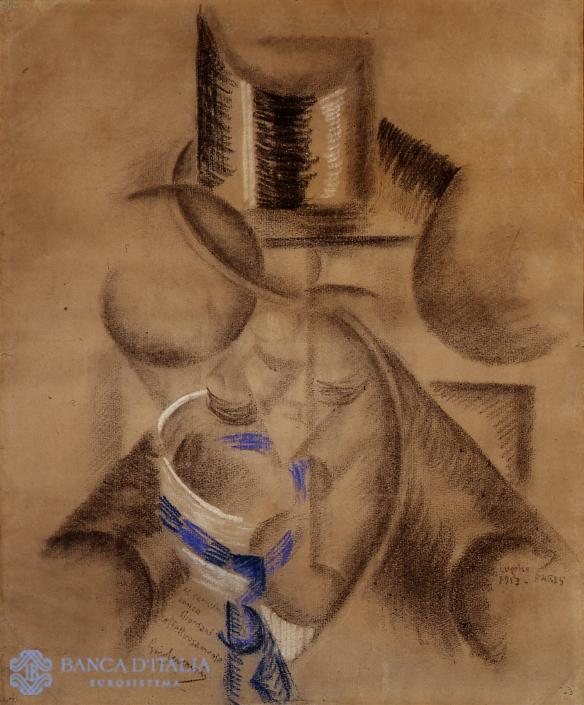

Ritratto del Dottor Giordani

Here we have precious testimony to Severini’s Futurist work in 1913. The date (even the month, July) and the name of the city where Severini was working (PARIS) are inscribed in the lower right, and to the left we have the dedication “Al carissimo amico Giordani affettuosamente Gino Severini” (to my dear friend Giordani with affection).

Painting

20th century AD

Portrait

Piazza di paese

The painting dates to the time of Marasco’s most enthusiastic adhesion to the Futurist movement, which he identified with the plastic dynamism of Boccioni. In this “village square”, the painter takes Boccioni’s method of de-composition into crude volumes in relief and a jarring movement, which combines in its “simultaneity” scraps of landscape in the background with buildings and figures at various levels.

Painting

20th century AD

Landscape

Paesaggio or Lirica al tramonto

The painting is from the Nuove Tendenze movement, a moderately avant-garde group that held its first – and only – show in Milan in 1914.

Painting

20th century AD

Landscape

Paesaggio futurista

Despite its small size, probably because in reality it was a sketch, this is an intense painting. The colours are heavy but animated by violent contrasts between complementary tones (above all reds and greens), and they saturate the forms fanning out in space.

Painting

20th century AD

Abstract

Mare velivolato

This is one of the tapestries – actually oils on tapestry canvas – that Balla displayed at the “Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs et Industrielles Modernes” in Paris in 1925, where Prampolini and Depero were also present. At that time the work was entitled “Mer, voiles, vent” (Sea, sails, wind).

Painting

20th century AD

Abstract

Espansione di luce + movimento

This fine work from the second decade of the 20th century is an early example of abstract painting inspired by the free triangular and circular forms of Giacomo Balla, intersecting in their celestial dances, but influenced as well by the more crowded, dynamic compositions of Gino Severini and the quite congested style of Umberto Boccioni.

Painting

20th century AD

Abstract

Dalie luminose

Balla worked on this theme between 1931 (the date of a first painting of dahlias, in a private collection in Rome) and 1945, when he executed his Splendore di dalie. Here, not only is the theme repeated, but the composition too resembles those earlier works, especially the 1945 painting.

Painting

20th century AD

Still life

Composition sur une courbe algebrique

This is an abstract work typical of the 1950s, when Severini went back to Futurism after the protracted figurative interlude of the interwar years. The allusion to an algebraic curve testifies to the artist’s lively interest in the relationship between form and “number,” already manifest in his “Du Cubisme au Classicisme” (1921).

Painting

20th century AD

Abstract

Colpo di fucile domenicale

Signed “Balla futurista” in the lower right corner, this is a typical abstract composition dating to the period when the artist had abandoned even the slightest figurative reference, leaving his imagination free to draw a series of curving arabesques, criss-crossing over the canvas to create chords of blues, yellows and greys alongside contrasts between blacks and reds, with startling white “voids”.

Painting

20th century AD

Abstract