During the 1970s, and especially towards the end of the decade, the highest and most innovative period of abstract painting can be said to have culminated throughout the world – at least as a unique or privileged domain for the most advanced artistic research. Its dominion – constantly challenged not only by a broad segment of the public and critics (and not just the most reactionary of them; see for all Roberto Longhi’s position in Italy), but also by parallel artistic experiments in figuration – ultimately remained undisputed. This is especially true when one considers overall developments in the visual arts from the start of the century up to the remarkable, almost simultaneous advent of conceptualism and pop art, and later of post-minimalist sculpture, which spread in various forms throughout Europe and America. With it, the traditional laws of sculpture also definitively entered into crisis as did the rigid separation that a century-old aesthetic speculation had traced between sculpture and painting.

As aesthetic theory evolved, however, the number and quality of the cases of permanence of the oldest languages remain striking. Some of the most important examples, as regards Italian art, are documented in the collections of the Bank of Italy. We owe their existence to members of previous generations who innovated without abandoning the old techniques; to artists that flourished in artistic grounds that were closer to the various declinations of conceptual art in Italy, and with it Arte Povera (which in reality was one of the formulations of international post-minimalism); and finally, to younger artists who in this period (the last thirty years of the century) were bent on recovering the canons of an abstract tradition of modern art.

Foremost among these were the experiments by Corpora, who in later years embraced a more intensively lyrical style; by Afro, inclined to a geometrical form of abstraction; by Scialoja, intent on recouping the free gestural expressiveness of 1956 and 1957 that he had abandoned in favour of the space-time “quantities” of the “Impronte”; by Perilli, Dorazio and Carla Accardi. All were members of Forma Nuova, all were intent on formulating an image still based on the standard identified by each in their early maturity: respectively, wild and Dadaist geometry, light and its transparency, and the sign submerged in the mantle of colour.

Of note in the second group are the works of Paolini, Calzolari and Gastini. Among the youngest of them, mentioned here only by way of example, we recall the rigorously geometrical paintings of Marco Tirelli and the transfigured, denuded “landscapes” of Silvio Lacasella.

Dal 1970 in avanti: altre forme dell’astratto

From 1970 Onwards: Other Forms of Abstract Art

Works of art

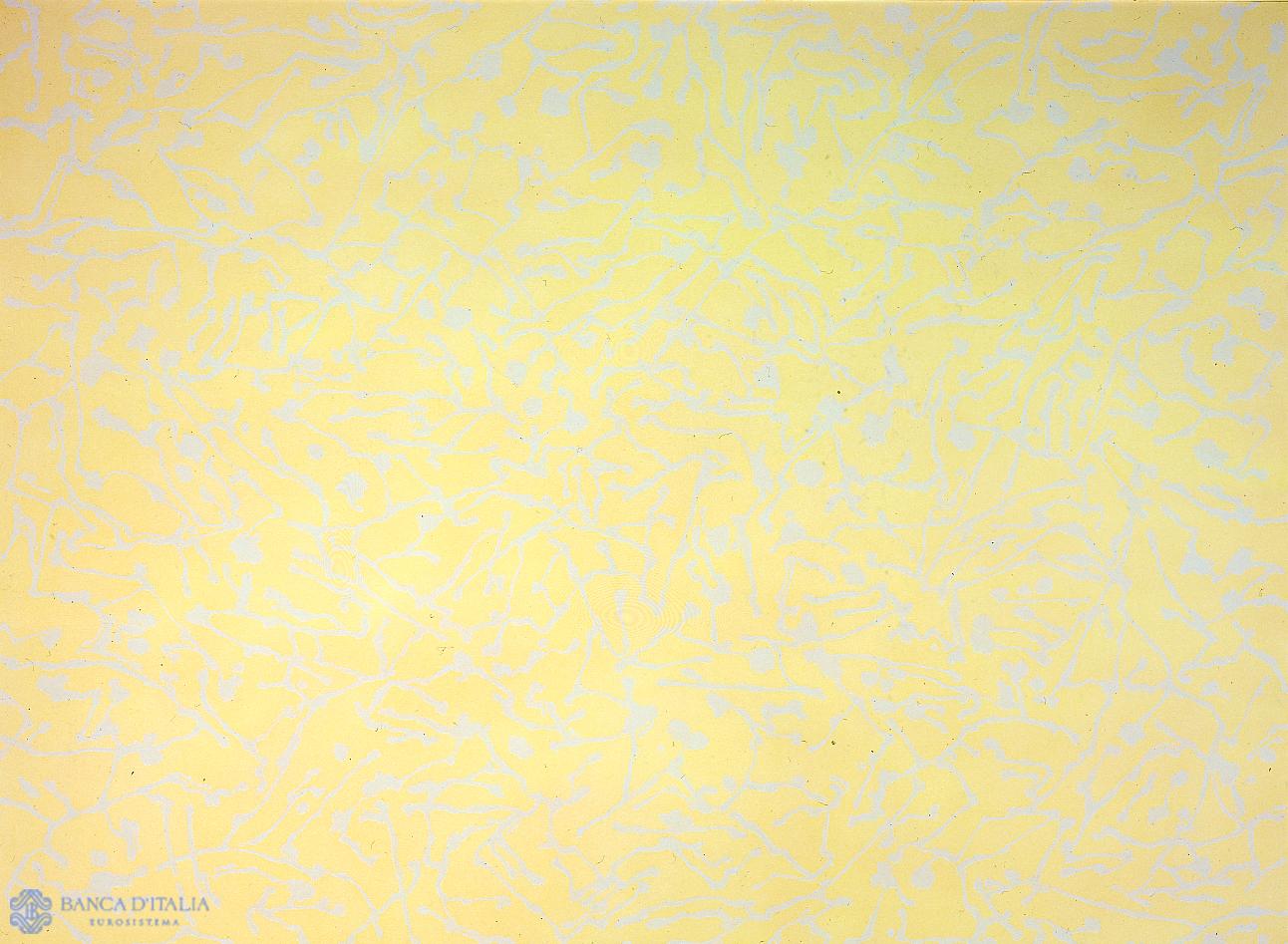

Vortice del vento verde

The title of the work alludes only to the background colour. Yet the full force of the emotional impact on the viewer comes from the matte yellow of the form that fluctuates in the pictorial space (as though it had been splashed onto the surface by a sudden gust of wind) and from the truly Matissian purple, used for the marks that drift aimlessly in the body of the ”figure” and the background.

Painting

20th century AD

Abstract

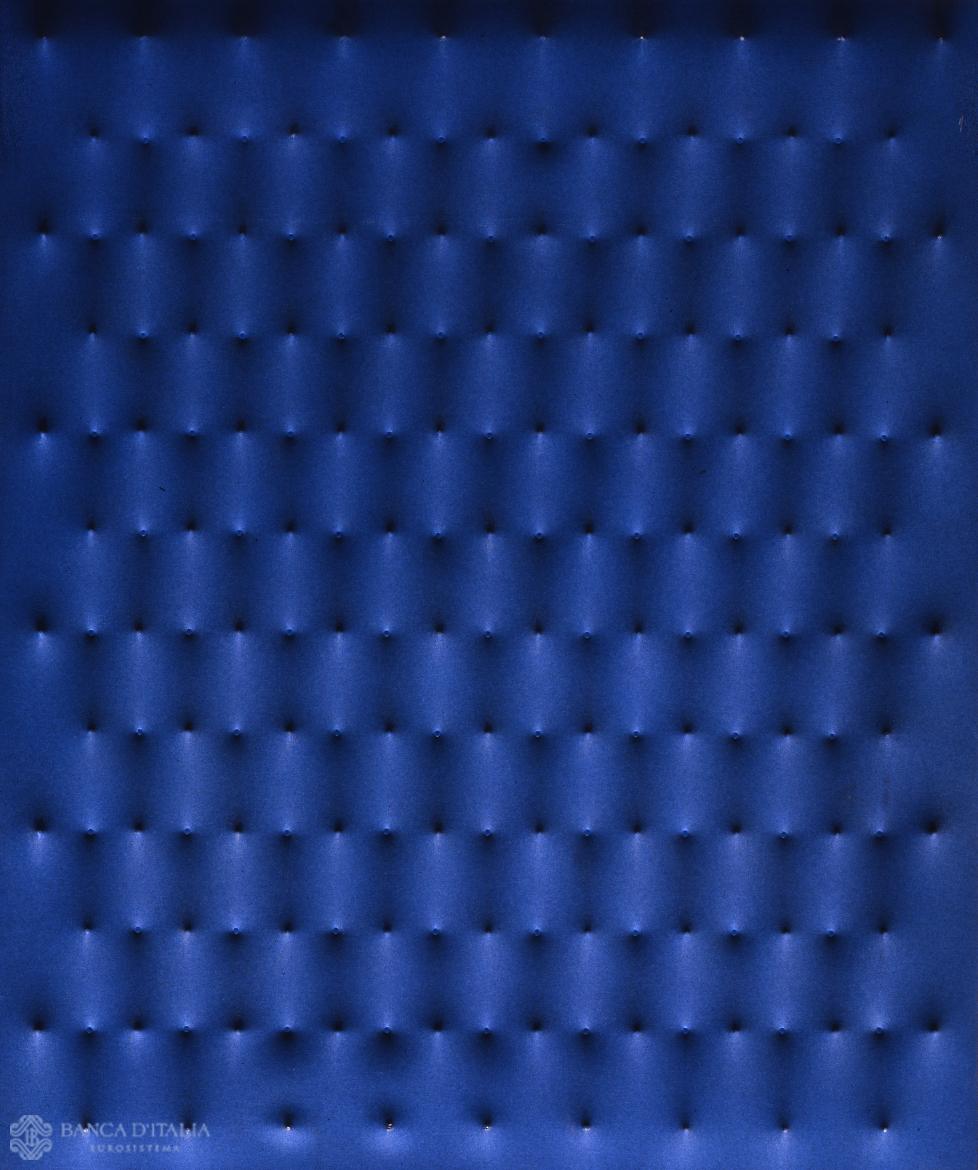

Superficie blu

The rigorously monochrome surface is raised at all four sides by symmetrically arranged nails placed at equal distances left and right, above and below, so that the canvas juts out from the frame.

Painting

20th century AD

Abstract

Soggetto astratto

Thickly clouded in a fine dust of material, the entire surface is saturated by the chromatic texture that fills every inch of the canvas. The myriad of colours that comprise its solid architecture, minutely tapped out onto the canvas, ultimately abandon their variegated nature to resemble a monochrome.

Painting

20th century AD

Abstract

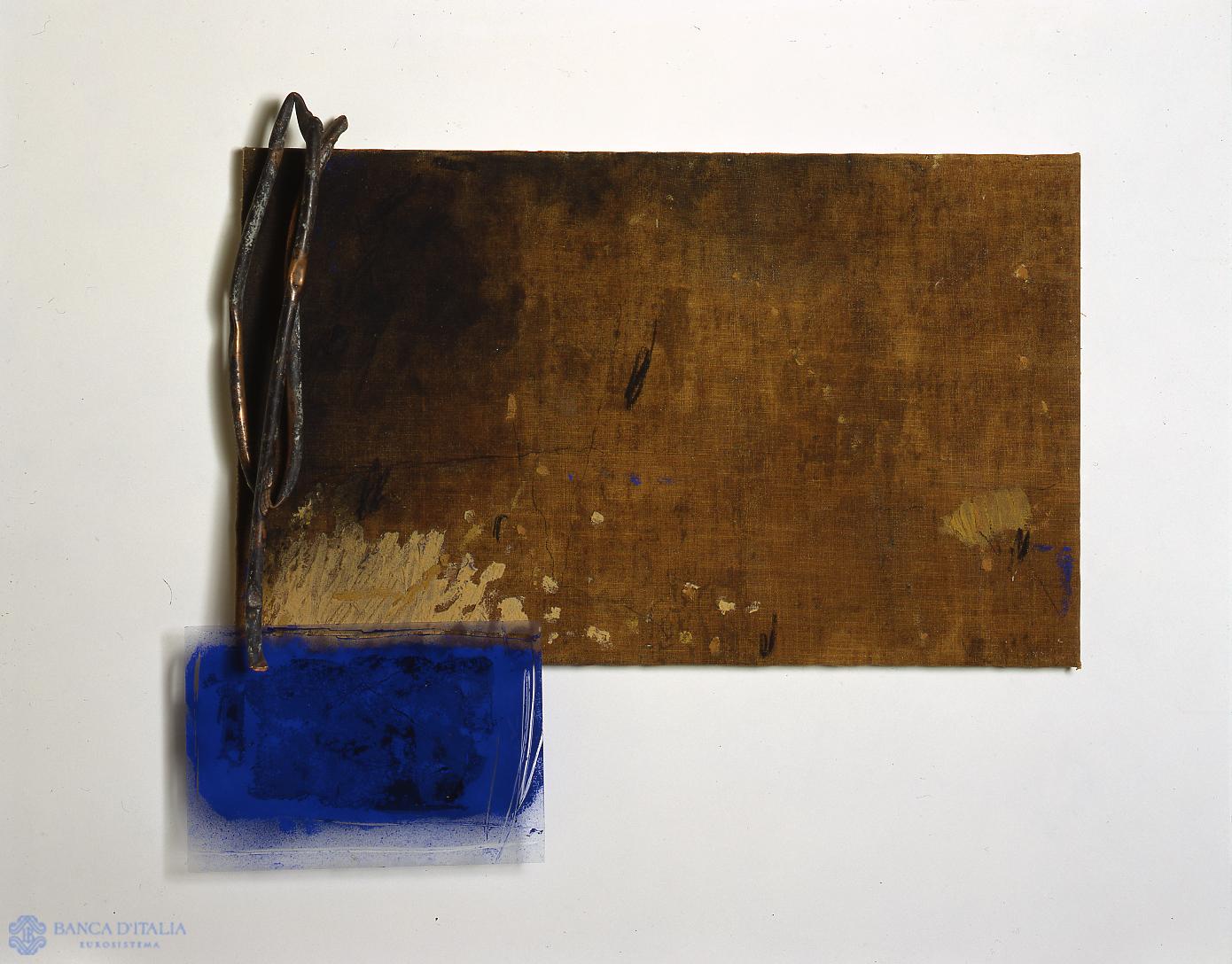

Untitled

La tela può essere, come spesso in Gastini, il supporto di una più antica pittura: erosa fino all’imprimitura, essa non conserva più nulla dell’immagine che ospitava, se non la memoria di quella primigenia intenzione a dipingere, a riempire “lineis et coloribus”, con linee e colori, la superficie.

Painting

20th century AD

Abstract

Untitled

Against a backdrop of plain red, tongues or stray wisps of smoke emerge from what appears to be a trellis. The result is an image that – more than from nature (with which Calzolari nonetheless said he wanted to maintain a relationship) – seems to come from a hallucination or a dream.

Painting

20th century AD

Abstract

Senza titolo (Orizzonte)

A sphere, magically suspended in space, gravitating in a uniformly dark area may be a warning or a threat, the naked presence of the most simple and perfect geometric figure bringing with it a genuinely telluric and primeval energy, is at the centre of the composition, borrowing its shadows, lights and hidden aspects from its depths.

Painting

20th century AD

Abstract

Senza titolo

Long thin strips of paper, previously doused in harmonious colours (the tones employed are ochre tending to light blue and to grey), are placed in a paratactical series on the small surface area: simple geometrical “quantities”, which seem foreign to any desire to find impetus, passion, or cries from the heart – as had long been the case in Scialoja’s work.

Painting

20th century AD

Abstract

Il paese della nostra infanzia

The image, enclosed by monochrome bands of browns, blues and greens that besiege it and progressively confine it to the centre, is composed of a jumble of imperfectly geometrical tesserae, which are intensely, almost joyously coloured and which, right in the middle of the work, comprise a kind of architecture of surface, vibrating with emotion, yet fixed and haughty.

Painting

20th century AD

Abstract

Impronte di paesaggio

Low down, a long strip of light crosses the entire painting. Below it, a narrow spit of land forms a far-distant horizon. At the centre, this duller-coloured land rises very slightly, as if stretching towards the light. This short-lived cresting is the sole movement in the entire canvas, the only element that takes it out of an immobile silence.

Painting

20th century AD

Landscape

Fuori tiro

In a vertical format – an unusual choice for the painter at the time, who was inclined instead to align his forms as though they were assembled along an imaginary horizontal thread – several imperfectly geometrical figures (circles, triangles, trapezoids, ovoids) rise up like a totem of ancient civilizations.

Painting

20th century AD

Abstract

Equivalenza

At the centre of the vast space of a white canvas, two perpendicular lines cross. Their meeting point, the exact focal point of the composition, is also the centre of two rectangles, they too drawn with perfect precision in thin black pencil line and occupying two growing portions of the space, re-echoing the dimensions of the canvas.

Painting

20th century AD

Abstract

Contractes

Irregular parallelepipeds and cubes crowd the airless space of the composition. The icy, pure colours that saturate them, untouched by shadow, struggle to chime with that deep-set dislocation of the image which the perspectival bodies appear to suggest.

Painting

20th century AD

Abstract